Students who practice metacognition are engaged in their learning and achieve more.

What is Metacognition?

Metacognition is our unique ability as humans to think about our thinking. As a definition, metacognition is the ability to recognize what we know and what we don’t know. The skills of metacognition include the ability to plan a strategy, be aware during the act and reflect on it afterward. It is being aware of one’s own thoughts, strategies, feelings, and actions – and how they affect others.

How can I teach Metacognition Skills?

In the book, Habits of Mind, authors Arthur Costa and Bena Kallick list thinking about thinking (metacognition) as one of the 16 Habits of Mind. Cleary, as one of the top habits of mind to develop, it is essential that we teach students the strategies and skills for metacognition.

1. Set meaningful goals.

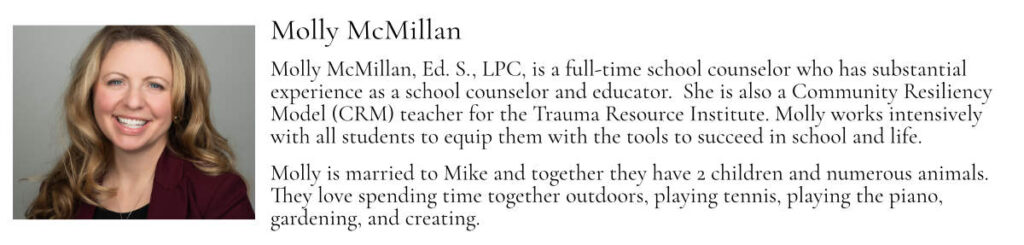

Goal setting is an important way to help students learn the skills of metacognition. First, students must consider what they want to accomplish and how they will do it. For the most part, meaningful goals need to be challenging, specific, and measurable. Using the SMART goals formula may help students plan big and act in small, specific ways. SMART goals are Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant, and Timely, which help students strengthen their metacognition. Click here to get your free SMART goals template.

2. Teach students the vocabulary to use the language of metacognition.

Students who learn both the inner language and expressive language of metacognition can discuss their thinking. In learning about metacognition, we want students to learn the habits of metacognition without getting stuck on the language – not having the vocabulary to express themselves. Share a list of words or synonyms that convey meanings similar to metacognition to allow communication with common terminology.

Learning the language of metacognition will help students be able to describe their thought processes. When students can explain their thinking, it gives a window into their mental processes. Cleary, students who are skillful in their ability to think about their own thinking can describe it and use it more often.

Teach students the language of metacognition.

3. Ask meaningful questions.

Powerful questioning strategies provide a rich opportunity for developing student metacognition. Ultimately, the goal of questioning is to help students develop the habit of curiosity. Teachers can model complex questions in language that students can understand. Furthermore, hearing and responding to complex questions builds the foundation in helping students become more apt in asking questions and posing problems.

Three characteristics of powerful questions to elicit metacognition include:

- Invitational language:

- “I invite you to…”

- “How might…”

- “As you consider…”

- The question uses plural to invite multiple concepts:

- “What are some of your ideas?”

- “What outcomes do you predict?”

- The question presumes positive capability:

- What are some of the benefits you will derive from engaging in this activity?

- As you set your goals, what will be some indicators that you are progressing and succeeding?

Questions that cause students to reflect on their thinking (metacognition) are especially effective:

- While you were listening, what was going on inside your head to monitor your understanding?

- As you read, what do you do when your mind wanders, but you want to remain on task?

- When you are working in a group, how do you know when you’re being understood?

- As you talked to yourself about this problem, what new insights were generated?

- What strategies are you considering?

4. Teach students how their brains are wired for growth.

Above all, students must believe that they can learn. When students learn the science behind growth mindset, they are more likely to be engaged in their learning. Our Growth Mindset Toolkit helps students learn about metacognition and how they can literally become smarter and strengthen neural pathways in their own brains.

5. Provide effective praise and feedback.

Process Praise

Feedback and praise can be tricky. If motivation is already evident, praise can be counterproductive because praise builds conformity and it makes students dependent on others for their worth. However, not all praise is to be avoided. According to Carol Dweck, process praise (praise for engagement, perseverance, strategies, improvement, and other character strengths) will foster hardy motivation. The best praise tells students what they’ve done to be successful and what they need to do to be successful again in the future. Examples of effective praise and feedbackinclude:

- “I can see that you really strived for accuracy with your project! Your improvement from one week ago is evident. You read the material over several times, provided evidence, and made accurate predictions. Your hard work shows!

- “I like the way you tried different strategies on that math problem until you finally got it.”

- “It was a grueling assignment, but you persisted and got it done! You sat at your desk and stayed focused until you finished. That’s impressive!”

- “Your paragraph is effective because you gave your reasons and support for your statements.”

- “This paragraph is well formed because you started with a topic sentence, and then provided evidence.”

Teaching metacognition is exciting because you won’t just be teaching content; you’ll be building a brain structure that will last a lifetime!